A Runner's Take on Occupy Wall Street

"Let us then place belief midway between certitude and nihilism. Let us see it characterized by trust, by affection, by a sense of novelty and by hope. Those traditions, especially religious, which have told us through the centuries that we know, for sure, the objects of our belief, have violated not only the character of genuine belief but also the mysterious openness of genuine religious experience. It is a deep tragedy that so much of our energy is expended in explicating and defending caricatures of our once viable traditions. ... [S]elf righteous interpretations of what is fundamentally inexplicable have divided us one from the other and cut us off from the human quest. In sociological terms, belief must cease its relationship to finality; it must turn to the future instead of the past." --John McDermott, The Community of Experience

I do not often write directly about politics on this blog, primarily because philosophy and running are escapes for me from an overwrought and underthought political scene. The connections between these three things--running, politics, and philosophy--are not obvious. They must be actively made, as the subtitle of the blog indicates. Something that is made can be unmade, and can be made poorly or well. Then, even if it is made well, it might be useful for some purposes and not others. At any rate, before beginning a political post, I just thought a sort of disclaimer might be in order--neither running nor philosophy necessarily lead in any logical way to certain political positions. The logical connections are always held and made through our thoughts, actions, temperaments, circumstances, efforts, and reflection. This is the "logic" of politics--the logic of ordinary life.

The above quote by John McDermott holds that belief is a midway sort of state. Running provides excellent examples of this. When we step to the starting line of a race, we have to believe in ourselves, believe that we are capable of running a certain time. This belief is something like a frame of mind that takes effort to hold and construct, and it guides our actions, gives us comfort, provides us hope, and--sometimes--allows us to achieve our goals. McDermott reminds us in this passage that we know beliefs by their function in experience. Their meaning and truth is found in how we hold them, and what they do for us. When we believe that we can run a certain time, we do not know it with certainty. Instead, we hold it with an attitude of trust and faith in our abilities to achieve. The race experience reminds us that the crucial quality of belief is not its having been determined to be true in the past, but the determination it gives us to fight for a possible future.

The beliefs that we hold at the starting lines of races are forged out of experience and effort. They are not arbitrary, and they are more likely to be realistic and serve their purpose of calling forth new capacities if they have been carefully and attentively made. The undertrained marathoner holds his belief in his ability to run a certain time in a very different way than the marathoner who has been through the trials of miles, and rightfully so. While the undertrained marathoner may be more certain of his ability to achieve his goal (depending on his ambitions), the well-trained runner has more faith in his belief--it means more to him; he holds his belief with affection and may call on this affect in times of distress.

As citizens of a democracy, we are asked to carry with us certain beliefs as well. These beliefs are well-known to all of us. We believe in equality, justice, freedom, and the pursuit of happiness. We are asked to hold these political beliefs together as a community, with affection. None of these ideals are certain; when we believe in these things, we are asked to do so in order that we bring them into being and hold them in place with our effort.

It is cheesy to suggest it, but the ideals of democracy are similar in form to race goals. They are not certainties that we accept because they have already been achieved. They are, instead, dreams that we will have to work towards with much effort.The important point, here, is that beliefs are not possessed; they possess us and move us. The marathoner proves his belief in his goal by being affected by it in the last miles of the race, by drawing on it to give him strength to continue to fight. So, too, do we prove our belief in democracy.

This is where McDermott's take on religion is helpful as well. We can practice politics as "explicating and defending caricatures of our once viable traditions," and we can give "self-righteous interpretations" of the meaning of democracy, intended to divide us. Or, we can abandon our relationship with finality in politics and offer ourselves up to democratic experience, which like religious experience is vague, indeterminate, and fundamentally open. McDermott's point is that we live into and with our beliefs; they are not made through argument. We can talk politics all we like, but in the end we have to run the race; we have to live together.

The analogy to running is limited, however, because a race is an individual endeavor in an artificial context while democracy is a community endeavor in a real and messy world. One of these things is much harder than the other. When we believe in democracy, we have to form common beliefs. We have to share experience. To create a deeply rooted faith in democratic life, we have to pass through experiences together, and we cannot control these experiences with a watch or break them into intervals. Often times these experiences break us down instead of making us stronger.

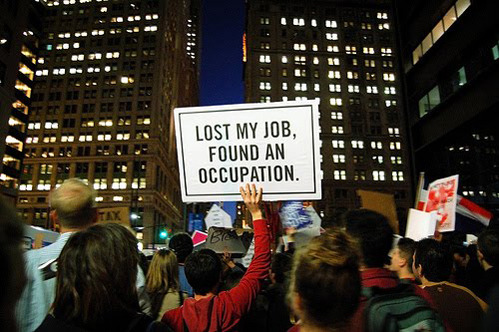

However, we can practice democracy. I believe this is the challenge that the Occupy Wall Street protests puts to us. It asks us how well we have been occupying our democratic ideals. As Matt Taibbi puts it in his excellent Rolling Stone article:

Running provides me a space apart from the chatter and difficulty of contemporary life. It helps me carve out time away from screens and chairs, walls and air-conditioned spaces. It reminds me of my capacity for pleasure and pain. For these reasons, I choose to believe that it is a practice of hope and self-development. But it can be equally argued that running is also a naive escape, a waste of energy, an self-satisfied act of leisure. I could see it this way, and if I did for long, I would stop believing in its transformative potential.

Like running and everything else in life, Occupy Wall Street is not perfect. It is both a challenge to genuine politics and an escape from it. Like running, it can be construed positively or negatively, and that choice will have consequences for its continuation. I make the choice deliberately to believe in it, to advocate and articulate its metaphors and vision, and to see it as a challenge to my own practice of democracy and the choices I make in living it out.

The challenge that Occupy Wall Street poses to us is both simple and extraordinarily difficult. It asks us this question: Can we form a society in which we are able to live together in a dignified, joyful, and deliberate manner?

I don't know the answer to these question with any degree of certainty, but as a runner and a human being I am well practiced in the living form of belief that works outside of the range of the certain.

|

| John McDermott |

I do not often write directly about politics on this blog, primarily because philosophy and running are escapes for me from an overwrought and underthought political scene. The connections between these three things--running, politics, and philosophy--are not obvious. They must be actively made, as the subtitle of the blog indicates. Something that is made can be unmade, and can be made poorly or well. Then, even if it is made well, it might be useful for some purposes and not others. At any rate, before beginning a political post, I just thought a sort of disclaimer might be in order--neither running nor philosophy necessarily lead in any logical way to certain political positions. The logical connections are always held and made through our thoughts, actions, temperaments, circumstances, efforts, and reflection. This is the "logic" of politics--the logic of ordinary life.

The above quote by John McDermott holds that belief is a midway sort of state. Running provides excellent examples of this. When we step to the starting line of a race, we have to believe in ourselves, believe that we are capable of running a certain time. This belief is something like a frame of mind that takes effort to hold and construct, and it guides our actions, gives us comfort, provides us hope, and--sometimes--allows us to achieve our goals. McDermott reminds us in this passage that we know beliefs by their function in experience. Their meaning and truth is found in how we hold them, and what they do for us. When we believe that we can run a certain time, we do not know it with certainty. Instead, we hold it with an attitude of trust and faith in our abilities to achieve. The race experience reminds us that the crucial quality of belief is not its having been determined to be true in the past, but the determination it gives us to fight for a possible future.

The beliefs that we hold at the starting lines of races are forged out of experience and effort. They are not arbitrary, and they are more likely to be realistic and serve their purpose of calling forth new capacities if they have been carefully and attentively made. The undertrained marathoner holds his belief in his ability to run a certain time in a very different way than the marathoner who has been through the trials of miles, and rightfully so. While the undertrained marathoner may be more certain of his ability to achieve his goal (depending on his ambitions), the well-trained runner has more faith in his belief--it means more to him; he holds his belief with affection and may call on this affect in times of distress.

As citizens of a democracy, we are asked to carry with us certain beliefs as well. These beliefs are well-known to all of us. We believe in equality, justice, freedom, and the pursuit of happiness. We are asked to hold these political beliefs together as a community, with affection. None of these ideals are certain; when we believe in these things, we are asked to do so in order that we bring them into being and hold them in place with our effort.

It is cheesy to suggest it, but the ideals of democracy are similar in form to race goals. They are not certainties that we accept because they have already been achieved. They are, instead, dreams that we will have to work towards with much effort.The important point, here, is that beliefs are not possessed; they possess us and move us. The marathoner proves his belief in his goal by being affected by it in the last miles of the race, by drawing on it to give him strength to continue to fight. So, too, do we prove our belief in democracy.

This is where McDermott's take on religion is helpful as well. We can practice politics as "explicating and defending caricatures of our once viable traditions," and we can give "self-righteous interpretations" of the meaning of democracy, intended to divide us. Or, we can abandon our relationship with finality in politics and offer ourselves up to democratic experience, which like religious experience is vague, indeterminate, and fundamentally open. McDermott's point is that we live into and with our beliefs; they are not made through argument. We can talk politics all we like, but in the end we have to run the race; we have to live together.

The analogy to running is limited, however, because a race is an individual endeavor in an artificial context while democracy is a community endeavor in a real and messy world. One of these things is much harder than the other. When we believe in democracy, we have to form common beliefs. We have to share experience. To create a deeply rooted faith in democratic life, we have to pass through experiences together, and we cannot control these experiences with a watch or break them into intervals. Often times these experiences break us down instead of making us stronger.

However, we can practice democracy. I believe this is the challenge that the Occupy Wall Street protests puts to us. It asks us how well we have been occupying our democratic ideals. As Matt Taibbi puts it in his excellent Rolling Stone article:

That, to me, is what Occupy Wall Street is addressing. People don't know exactly what they want, but as one friend of mine put it, they know one thing: FUCK THIS SHIT! We want something different: a different life, with different values, or at least a chance at different values.The idea of occupying our democracy resonates with old American ideas. It reminds us that our beliefs are not precious gems to be fondled and protected or weapons with which we destroy our ideological opponents. Our beliefs are our deliberate ways of living; they are ways of occupying the world. When Thoreau wrote that he went to the woods to live deliberately, he was, in a sense, trying to occupy his life. This is what it means to be a free individual, to occupy your life, to occupy a place, to occupy a community, and to occupy your beliefs. The Wall Street protesters have chosen a different sort of wilderness to test their capacity for deliberation. They are not looking to take control of a single life, but simply asking whether it is possible to live together without fear in very heart of the democratic experiment.

There was a lot of snickering in media circles, even by me, when I heard the protesters talking about how Liberty Square was offering a model for a new society, with free food and health care and so on. Obviously, a bunch of kids taking donations and giving away free food is not a long-term model for a new economic system.

But now, I get it. People want to go someplace for at least five minutes where no one is trying to bleed you or sell you something. It may not be a real model for anything, but it's at least a place where people are free to dream of some other way for human beings to get along, beyond auctioned "democracy," tyrannical commerce and the bottom line.

Running provides me a space apart from the chatter and difficulty of contemporary life. It helps me carve out time away from screens and chairs, walls and air-conditioned spaces. It reminds me of my capacity for pleasure and pain. For these reasons, I choose to believe that it is a practice of hope and self-development. But it can be equally argued that running is also a naive escape, a waste of energy, an self-satisfied act of leisure. I could see it this way, and if I did for long, I would stop believing in its transformative potential.

Like running and everything else in life, Occupy Wall Street is not perfect. It is both a challenge to genuine politics and an escape from it. Like running, it can be construed positively or negatively, and that choice will have consequences for its continuation. I make the choice deliberately to believe in it, to advocate and articulate its metaphors and vision, and to see it as a challenge to my own practice of democracy and the choices I make in living it out.

The challenge that Occupy Wall Street poses to us is both simple and extraordinarily difficult. It asks us this question: Can we form a society in which we are able to live together in a dignified, joyful, and deliberate manner?

I don't know the answer to these question with any degree of certainty, but as a runner and a human being I am well practiced in the living form of belief that works outside of the range of the certain.

Thank you, Jeff. One of the biggest challenges for me is occupying my beliefs and ideals. The older I get the more I find myself scoffing at them, if only emotionally, much like the RS writer originally scoffed at the OWS protestors. But, like him, I try to pull myself back and acknowledge the uneasiness of living so far outside what I know is true about how I should live and how the world should be.

ReplyDelete"I swear it upon Zeus an outstanding runner cannot be the equal of an average wrestler." --Socrates

ReplyDeleteTo run our best, to live our best, to philosophize well, we gotta wrestle through it all.

this is the part i struggle with -- "a bunch of kids taking donations and giving away free food is not a long-term model for a new economic system." they're out there protesting, but they don't have any better ideas. if you don't like it, leave! gah! get a job! you're living in a fantasty! that's not how the world works!

ReplyDeletebut, i see what you're saying here, i think. seems you're saying, maybe "that" is not how the world HAS TO work, or even, possibly, is SUPPOSED TO work.

so, i find what you've said very interesting and i appreciate how you've presented it clearly. you've given me something to think about, and i like to think. so, thanks!

Dear ace,

ReplyDeleteThanks for being brave enough to comment seriously on a political piece. Socrates thought the first philosophical virtue was courage, and I agree with this.

The only part of your post I would quibble with is this thought that "they don't have any better ideas." I don't know if this has yet been determined. Plus, even if they don't have better ideas, perhaps the better reaction would be to join in and talk to the folks and help come up with better ideas.

That said, I understand some frustrations you articulate. The OWS protest force us to take a stand on them, to react to them. We can dismiss them, we can advocate for them, we can criticize them, we can belittle them, we can blindly adore them. There are many possible reactions, and each of these reactions, in a small way, determines something about our future lives together in this increasingly small country.

yes, that's a weak spot for me - "they don't have any better ideas". it's a bit of a knee-jerk reaction.

ReplyDeletethe capitalist system doesn't always work but nothing always works and part of growing up is that we just learn to live with it, live within it. whatever 'it' may be.

yikes. that's depressing. that's not the person i meant to become. what happened?

here is a group, maybe i am in it, telling these dissenters if they don't have any better ideas, then their energy is misspent - that the only thing that gives value to their energy is to channel it into concrete plans.

do i really believe that? do i really believe that the only valuable dissent is coherent, managed dissent?

yikes.

p.s. brave? me? well, now....

ReplyDeleteThe proof of the worthiness of this effort will be if anything positive comes from it and that will apparently take time.When people protested against the Vietnam war way back when,many believe their efforts led to an ending of that war. That was a positive result.

ReplyDelete