Running as Work and Play

This way of considering play and work leaves little space for dignified human activity. It divides life into moments of distracted entertainment that lead nowhere and periods of unsatisfying labor carried on under the compulsion of ends that are external to the activity itself.

In Democracy and Education, John Dewey rethinks the relation between play and work. He asserts that both play and work seek results; both are oriented towards ends. The primary difference between the two forms of activity is the proximity of the ends that they have in view. The ends of play are proximate and more easily achieved. Play feels freer and more plastic because the proximity of the ends of play allows the free and imaginative selection of multiple means to those ends. The ends of work are remote and require more rigorous planning. Discipline and effort are more central characteristics of work because the more remote and precarious nature of its ends requires careful and deliberate selections of the means to that end as well as discipline to apply those means over a longer period of time.

Therefore, for Dewey, play and work are not opposites but lie on a continuum that is determined by the proximity of the ends of the activity. Play is freer and more spontaneous due to the fact that the end achieved is clearly in view. Work requires discipline and effort due to the fact that the ends it pursues are distant and sometimes in doubt.

As runners know, one of the strange and compelling things about running is its status as somewhere between play and work. We get the satisfaction of both work and play.

Each run is a type of play. Its ends are proximate and can be fulfilled freely and in a variety of ways. We can choose our route, choose to do a workout or an easy run. We can choose to run alone or with a group. As we run, we can choose almost anything to think about, to chat about, to watch. We get to feel the weather, the strength in our legs, cleansing sweat. All of this is very much like play, as each run -- especially for the experienced runner -- is like a jazz orchestra of sensation to be enjoyed. As in all play, each run itself surprises us with its freeness and spontaneity. We return home more often than not with more energy than we left, having experienced true recreation. This is the proximate end of each run, the play function of each run.

Equally, however, running gives us a chance to do work. When we choose a goal in running, we are usually careful to place it just beyond the known horizon of our capabilities. We make sure, in other words, that the goal is sufficiently remote. We want goals that are difficult, ones that can't be captured spontaneously or freely but have to be achieved through choices, effort, planning, and intelligence. Just as much as we talk about running being something that we enjoy and do for fun, we also talk proudly about the sacrifices we make for our goals, the pain and the grind of training, and the way in which we are tormented by our lack of achievement.

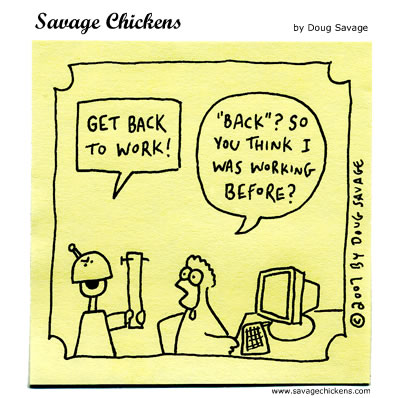

|

| Louis Armstrong at work/play. |

There are, of course, wider lessons to be drawn. Running can teach us that work and play are at their best together. The best stretches of life flow with a rhythm in which the proximate ends of our activity sustain us and direct us towards the more remote ends.When these rhythms are out of whack, life feels like stretches of mindless drudgery interspersed with empty interludes of entertainment. Play feels like wasting time, and work feels like pure sacrifice, only externally related to what we want to get out of life. If we can find an interactive balance between work and play, we can avoid such a divided and empty life.

Dewey comments that finding ourselves in such a divided and empty state is the sign of life under conditions of coercion. Freedom, on the other hand, is something like a state of harmony between our proximate ends and our more remote aspirations.

It's not hard to see the value of Dewey's conceptions of freedom and coercion today. The connection between our distracted forms of play and our collective anxiety about the more remote ends and directions of society seems too obvious to ignore. Is it any wonder that as the value of work becomes further and further reduced to external economic ends that we find it more and more difficult to concentrate? Should we be surprised to find our forms of play diminished to launching angry birds on computer screens when the ends of work bear no relation to our day to day living?

If, as running shows us, humans are at their best when their work and play are fruitfully mixed and interactive, why do we continue to oppose work and play? Such a philosophy drives us to distraction in the short term and undoes our ability to take satisfaction in the long term projects of our lives. A dignified and joyful life will always require the balancing of remote ends with proximate ends. Running shows us that such a balance can be found -- and lost -- and also regained again.

By the time I reached the end, I found the substance of all my comments in the post itself.

ReplyDeleteI've always been at my best when free and playing and most "blocked" and paralyzed when I felt coerced.

Great post.

As always, thanks for reading and commenting.

Delete"It becomes mere entertainment and hollow escapism."

ReplyDeletethis is what i am currently WORKING to overcome in my running.

Ha ha, very nice.

Delete"Work and play are at their best together", but sometimes not if one's work is running. I'm thinking of the unknown runners collecting cheques in Crazy-8s or the known ones lining up for twice yearly paydays at major marathons. Does the pressure side of the work detract from the playfulness of proximate running?

ReplyDeleteAs a person who works in order to play at running, I love "this peculiar balance between play and work that makes running such a satisfying human activity." The remote ends of running can also be near or far - from season's bests to lifetime PBs (which in my case took 10 years to attain), to event goals, to 'out there' goals (run a marathon in every state), or for me now, age-group best times. Running's a fun thing to do!

My goal to BQ was just what you describe: the perfect balance between work and play. I was enjoying myself immensely as I edged a little closer and closer still. Then, with this back injury, the balance has tipped way over to the work side. I hate the doctor/PT/chiropractor visits. I hate the constantly changing rehab routines. I hate the money I'm spending. I'm back to running, but I'm not going far or fast enough. I keep telling myself this is a means to The Goal, an unplanned side-track. I'm hoping I can keep the positive talk going long enough to get through it, because I don't know what I'd do without the goal. I want the play piece back.

ReplyDeleteGreat post as always!