Running Beyond the Limits of Language

In The Blue Book, which was a sort of collection of lecture notes that he compiled in lieu of writing a book for Russell, Wittgenstein writes the following, ruminating on a common theme of his--the perils of communication:

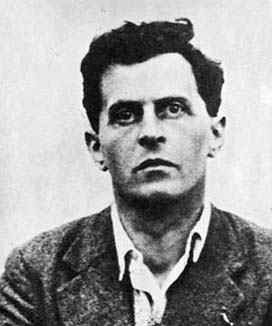

You might say, then, that Wittgenstein was a sort of anti-philosopher. He painted a picture of philosophers as isolated and largely befuddled men (and they were all men) who wasted their thoughts on questions that hardly made any sense, challenging them (and still us today) to reflect upon the habits and contexts that sustain philosophical reflection and inquire into the actual value of those habits for life.

Of course, almost every great philosopher in history was an anti-philosopher in the sense that philosophy makes progress by waking reflection up to reality, shaking it from its daydreams or its enslavement to corrupting influences and liberating it to the service of the enrichment of life. So, in this sense Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations are both a critical investigation into whether philosophy makes any sense at all and a deeply affirmative philosophical investigation into the relevance of our intellectual achievements.

Yes, language bewitches. Our forms of expression, philosophical and otherwise, betray us. Language points, gestures, slips, errs, confuses. But it also is, as Dewey wrote, the "tool of tools," lying at the very heart of human intelligence. The same duality lies at the heart of thinking. Our capacity for reflection can be brought to bear on solving real and pressing problems, or it can be used just as easily to distract ourselves from problems.

The difficulty, of course, is that it is not always easy to distinguish productive thought from distractive thought. Perhaps art demonstrates this tension best: beauty, art, and the artist seem something impractical and perhaps less than necessary while simultaneously coming off as the highest form of human activity. Art doesn't solve any problems--more often it poses them--but on the other hand a world without art, without beauty for its own sake, seems like a world without purpose. Art seems, strangely, both a distraction for life and central to it.

Politics is another example. We are in the middle now of intense political conflict over what to do about the economy. It seems like all of this reflection and debate ought to be productive, right? We have the best minds (all minds, really) focussed on the question of what to do. We are thinking hard and focused directly on the problem. At the same time, many economists argue that the economy is suffering precisely because because of the political debate--the economy is struggling because we take it to be a political problem! What to do about this? Reflect more on the economy? Debate more? Argue more? Will this really help? Here, reflection on a problem seems not only of dubious value, but possible of negative value.

As you can see, we are always "up against trouble caused by our way of expression."

Here is where running comes in. Running is an activity that requires no language. In fact, when pursued at its highest intensities, it makes language impossible. My memories of my best runs and races are always mute, the linguistic part of the brain having been abandoned for different modes of attunement. When we run, we watch the world with an eye that points in two directions. We look out, ahead to the horizon or downwards to the passing terrain. We also look in, feeling our bodies, the rising surges of sensation, the drifting lines of feeling. Most of what we see and feel when we run cannot be put into words but can be experienced with powerful depth.

Technology, the web, the knowledge economy have created a world that feels increasingly virtual and representational. The world itself confuses and bewitches like language. The dream-screens into which we peer bring us thoughts from who knows where. A run is an escape into a different sort of world, one which feels less full of instruments, tools, and signs. The sensations come scrubbed of their representations, and for this reason they are simultaneously more vague and more vivid.

In his recent post, Zach wrote well of running as a practice of positive freedom, a way to grow into one's self. But running has also always been a form of escape, perhaps the first form of escape, before we learned to dream away our lives. As escape, it is a practice of negative freedom, a practice of liberation from the clang and confusion of representation, the persistent demand that life, our actions, and our values make sense.

In this way, perhaps, running is like Wittgenstein's philosophy. It does not offer a coherent plan or life strategy; it doesn't pretend to completeness or offer the secrets to a well-lived life. What it gives us is a way out of the plans and meanings and senses that have begun to seem virtual and hollow. A run gives life no meaning. It simply reminds us that beyond the sense that life makes, there is so much more life.

When we look at everything that we know and can say about the world as resting on personal experience, then what we know seems to lose a good deal of its value, reliability, and solidity. We are then inclined to say that it is all "subjective"; and "subjective" is used derogatorily, as when we say that an opinion is merely subjective, as a matter of taste. Now, that this aspect should seem to shake the authority of experience and knowledge points to the fact that here our language is tempting us to draw some misleading analogy. This should remind us of the case when the popular scientist appeared to have shown us that the floor which we stand on is not really solid because it is made up of electrons.It seems we are always up against this trouble--the trouble of language. Language bewitches us, creating mysteries through its metaphors, mixing indiscriminately resonances, meanings, and connotations. Wittgenstein's view of philosophy was that most of the problems that it dealt with were a consequence of pernicious habits of expression rather than deep metaphysical mystery. He taught philosophers not to think quite so deeply and mystically--to look for the answers to their great and enduring questions in habits of expression that were imbedded in speech acts that had no clear consequences. Thus, the way to address many of the lasting philosophical problems was not to penetrate to the mystical core of reality with the mind, but instead to wonder practically and specifically about why we were worrying about these things in the first place. What habits of speaking generated these questions? What forms of life propagated and sustained them?

We are up against trouble caused by our way of expression.

Of course, almost every great philosopher in history was an anti-philosopher in the sense that philosophy makes progress by waking reflection up to reality, shaking it from its daydreams or its enslavement to corrupting influences and liberating it to the service of the enrichment of life. So, in this sense Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations are both a critical investigation into whether philosophy makes any sense at all and a deeply affirmative philosophical investigation into the relevance of our intellectual achievements.

Yes, language bewitches. Our forms of expression, philosophical and otherwise, betray us. Language points, gestures, slips, errs, confuses. But it also is, as Dewey wrote, the "tool of tools," lying at the very heart of human intelligence. The same duality lies at the heart of thinking. Our capacity for reflection can be brought to bear on solving real and pressing problems, or it can be used just as easily to distract ourselves from problems.

The difficulty, of course, is that it is not always easy to distinguish productive thought from distractive thought. Perhaps art demonstrates this tension best: beauty, art, and the artist seem something impractical and perhaps less than necessary while simultaneously coming off as the highest form of human activity. Art doesn't solve any problems--more often it poses them--but on the other hand a world without art, without beauty for its own sake, seems like a world without purpose. Art seems, strangely, both a distraction for life and central to it.

Politics is another example. We are in the middle now of intense political conflict over what to do about the economy. It seems like all of this reflection and debate ought to be productive, right? We have the best minds (all minds, really) focussed on the question of what to do. We are thinking hard and focused directly on the problem. At the same time, many economists argue that the economy is suffering precisely because because of the political debate--the economy is struggling because we take it to be a political problem! What to do about this? Reflect more on the economy? Debate more? Argue more? Will this really help? Here, reflection on a problem seems not only of dubious value, but possible of negative value.

As you can see, we are always "up against trouble caused by our way of expression."

Technology, the web, the knowledge economy have created a world that feels increasingly virtual and representational. The world itself confuses and bewitches like language. The dream-screens into which we peer bring us thoughts from who knows where. A run is an escape into a different sort of world, one which feels less full of instruments, tools, and signs. The sensations come scrubbed of their representations, and for this reason they are simultaneously more vague and more vivid.

In his recent post, Zach wrote well of running as a practice of positive freedom, a way to grow into one's self. But running has also always been a form of escape, perhaps the first form of escape, before we learned to dream away our lives. As escape, it is a practice of negative freedom, a practice of liberation from the clang and confusion of representation, the persistent demand that life, our actions, and our values make sense.

In this way, perhaps, running is like Wittgenstein's philosophy. It does not offer a coherent plan or life strategy; it doesn't pretend to completeness or offer the secrets to a well-lived life. What it gives us is a way out of the plans and meanings and senses that have begun to seem virtual and hollow. A run gives life no meaning. It simply reminds us that beyond the sense that life makes, there is so much more life.

This makes me want to run...not communicate. You are right,running is so much more straight forward than trying to make yourself understood. It is refreshing for that reason. Thanks for reminding me of that.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Jeff. I think it's in my nature to try and "use" the run to work out practical problems, those that presented themselves before the run and those that I anticipate in the coming day.

ReplyDeleteAt some point, it becomes all muddled as I start to imagine unlikely problems, encounters and conversations. It becomes messy. That's when I sort of shake it off, and realize it's best to leave it to the "rising surges of sensation, the drifting lines of feeling."

Running can be a panacea for the neurotic, if only he or she will let go.

Even verbalized prayers -- such as can be uttered while running -- at some point can become redundant, and I find that offering up the run and my self can itself be a profound prayer.

Dear Anonymous poster,

ReplyDeleteThanks for commenting and reading!

Nader: Nice points, and I like the connection to ritual and prayer. It seems to me that precisely at the point that prayer becomes ritualized, it changes its communicative function and begins to operate "beyond sense" in much the same way that running and life itself often operates.

Hey, just stumbled across this blog about an hour ago and have been poking around. Lots of good thoughts and writing on here!

ReplyDeleteDecided to post about this one because I'm a fan of LW. I like the analogy you draw things together with at the end, essentially that running and positivism can both be a form of escape from problems associated with language (from over-articulating our internal lives, from traditional philosophical problems which happen when terms transcend their conditions of significance).

However, I found that the paragraph where you first bring in running (next to the great picture of Bekele marshalling the troops!!) obscures this point a little bit. It's not that running can't be articulated - from a Wittgensteinian point of view the sensations of running are on a linguistic par with any other sensations. If such language games haven't developed, that's because a runner's internal monologue is not 'common and conspicuous enough to be talked of often' or 'near enough to sense to be quickly identified and learned by name', at least to most people.

Indeed, when we read for example certain passages in Once A Runner, or even on your blog, we start to see verbal constructs that capture the sensations of distance running being developed. Just as a child learns 'red', and what it refers to by situations with various red objects. Of course in our case the requisite intersubjectivity can only be achieved by a certain group of oddballs familiar with these particular referents!

Anyway, sorry for the long and nitpicky post, but I just wanted to clarify the point that running is not immune to language in some way that most activities aren't, but just that we tend to verbalize less while doing it. As a runner and a LW fan, seemed like an important distinction. ;)

And, I almost hesitate to make a comment about politics, but while I'm at it...

ReplyDeleteThe economy isn't suffering because people are thinking about the best thing to do, but because the political system doesn't allow us to do the best thing. Reflection is a part of politics, but the problem is the imperfect information/special interest part of politics, not the reflective part. So I disagree that reflection on political problems is of negative value (except insofar as it is frustrating in its pointlessness!).

I do agree that just as Wittgenstein points out shortcomings in our language, there are definite shortcomings in our political system as well. Interesting parallel! :)

MM--

ReplyDeleteYou first point is excellent, and I want to agree entirely--which makes me nervous as a philosopher! I agree that I shouldn't have claimed impossibility and focused more on the fact that we don't want or need to articulate everything. Well said.

Your second point is also well taken. Perhaps what is most frustrating is that the political system divorces political reflection from political problems--i.e. it leads us to attack each other in frustrating ways instead of reflecting on our problems. (Note that I only said that political reflection is possibly of negative value. It would have been clearer to say that reflection is not always positive and sometimes even leads to frustration, anger, apathy and other negative outcomes.)

I really appreciate these comments, and I am really glad you found the blog. Send me an email at logicoflongdistance@gmail.com. We need to get you set up as a guest blogger!

Jeff,

ReplyDeleteHaha yes, never agree entirely! This is perhaps the first lesson of philosophy! ;)

I now see that we didn't necessarily disagree about the role of reflection in politics. Thank you for expanding and clarifying. I agree (er, tentatively and provisionally!) that the 'divorce between political reflection and political problems' is very real and very frustrating. Running and philosophy can both be great escapes from this frustration!

Thank you for your great responses. And I am honored by the invitation to guest blog! I am really impressed by the wide collection of interesting and original thoughts that you've expressed here about running and its interaction with philosophy.