Ryan Hall, Tim Tebow, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

"Men move between extremes. They conceive of themselves as gods, or feign a powerful and cunning god as an ally who bends the world to do their bidding and meet their wishes. Disillusioned, they disown the world that disappoints them; and hugging ideals to themselves as their possession, stand in haughty aloofness apart from the hard course of events that pays so little heed to our hopes and aspirations. But a mind that has opened itself to experience and that has ripened through its discipline knows its own littleness and impotencies; it knows that its wishes and acknowledgments are not final measures of the universe which in knowledge or in conduct, and hence are, in the end, transient. But it also knows that its juvenile assumption of power and achievement is not a dream to be wholly forgotten. It implies a unity with the universe that is to be preserved. This belief, and the effort of thought and struggle which it inspires, are also the doing of the universe, and they in some way, however slight, carry the universe forward. A chastened sense of our importance, apprehension that it is not a yardstick by which we measure the whole, is consistent with the belief that we and our endeavors are significant not only for themselves but in the whole."

--John Dewey, "Existence, Value, and Criticism" from Experience and Nature

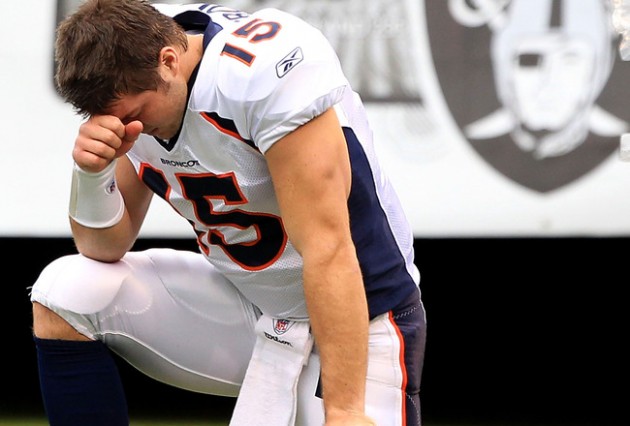

Much ink has been spilled lately on the role of religion in sports. The entire country, it seems, has been transfixed by Tim Tebow, as he marched onward in the NFL playoffs. Through his play, demeanor, and public pronouncements of faith, Mr. Tebow has asked us all to consider such strange questions as whether or not God takes sides in football games, whether religious faith can make you a better athlete, what role religion ought to play in public life, and exactly how much credit we should give (or take away) from Tebow for so boldly proclaiming his faith in our increasingly secular and pluralistic culture.

Before Tebow hit the NFL, we few followers of the sport of distance running already had our Tebow. Ryan Hall and Tim Tebow seem to carry themselves similarly. After he finished 2nd in Saturday's marathon trials, he talked about how God was with him for every step of the race. Hall left his coach, Terrence Mahon, and now talks about waking up in the middle of the night inspired by the insights that God has given him into his training.

It's important to remember that there have been a lot of great athletes who have reached the pinnacle of their sports without the same sort of evangelical zeal. History shows that this sort of open faith is unnecessary for athletic success. However, both Hall and Tebow are so convinced that their faith is the key to their performance that it is hard not to take their personal conviction seriously. The question they pose to us is simple, but stunning: "Would I be a better athlete--not to mention a better person--if I had the same sort of religious faith that Hall and Tebow did?" Both Hall and Tebow basically answer in all their words and actions, yes. They see their role as celebrities as a platform given to them by God in order to celebrate him and spread his messages.

Today we also celebrate a man who put his faith into action, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Reflecting a bit on his life, remembering the ends to which he put his religious belief, helps to put the question that Hall and Tebow pose to us in perspective. While both Tebow and Hall contribute to charity and practice good works, King took the lessons of Christianity to heart in a more profound way, focusing not on charity but on social justice. While Tebow and Hall speak eloquently of the power that God gives them in their personal lives and as they practice their professional sports, King preferred to emphasize the duties that God imposed upon him as a believer.

It seems to me that King's connection with God was much less personal and individual than the way Tebow or Hall characterize their connection. For King, God's greatest gift to humanity was the ability to dream of social justice, and to give ourselves in effort to actualize that dream. King was not content to proselytize through celebrity or games; these are essentially conservative social functions. He used his radical vision of religion to push an entire nation to change itself in fundamental ways.

When King was assassinated, he had moved through the issue of race to the issue of poverty, which he thought was a more fundamental concern. The day that he was shot, his approval rating stood at 30%. My grandmother, a Nashville native, spoke to me just last week of how much people hated Dr. King in her community--a fact that she herself had almost forgotten in the 44 years since his death.

When King was assassinated, he had moved through the issue of race to the issue of poverty, which he thought was a more fundamental concern. The day that he was shot, his approval rating stood at 30%. My grandmother, a Nashville native, spoke to me just last week of how much people hated Dr. King in her community--a fact that she herself had almost forgotten in the 44 years since his death.

In the passage above, John Dewey draws our attention to two psychological extremes, both of which stem from the same weakness. The first extreme is overestimating our own power, believing that we are gods or that a god will bend the world to our own plans. The second extreme is disillusionment with the world: seeing the world as fundamentally broken and withdrawing from it to a dream world of idealism. I see both of these extremes in the internet discussions of the meaning of Tebow and Hall's successes. The "haters" impugn their idealism, calling them crazy. The "lovers" see in Tebow and Hall confirmation of their own personal vision of reality, evidence of the transformative power of Christianity.

Dewey was not a Christian, and neither am I. But he was a clear-eyed examiner of social life and the role of religious sentiment in it. I think he would have found both of these ways of seeing Tebow and Hall lacking.

The mature balance towards which Dewey pushes us, and which I would like to encourage as well, neither puts too much power in faith, nor too little. Athletes like Tebow and Hall can remind us of what Dewey calls "the juvenile assumption of power and achievement." Their naive belief in themselves and in their personal vision of the world is refreshing in a cynical age. But we should not forget that our cynicism and the tolerance that it can give us for other points of view and working through difficulties is also hard won--the product of ripened experience. This is why, for me, King provides a more complete vision of the role of faith in life. His faith focused not only on power and achievement, but turned him steadfastly towards the most difficult of problems: how to create lasting change for the better in this world.

King's democratic faith had an element of the blues in it. Cornel West called this element of faith a capacity for "tragicomic hope" -- the ability to dwell amid suffering, to confront the tragedies of the human condition, and to make a song out of it. Tebow and Hall are young, still. They are great representations of juvenile power, and they ought to inspire us with their power and performance. But King, to my mind, is the greater exemplar of a fully mature human faith. Like the man from whom his religion draws its power, his life is not a reminder of the power of the individual to forge its own destiny or do what he puts his mind to. The lesson is deeper. His life and faith is a reminder of the work that is left to be done on behalf of humanity: the duty of social justice.

King's life and faith preached "a dangerous unselfishness." He taught that the clear-eyed recognition of our duty to humanity is the mark of a belief that fully deserves to call itself religious.

--John Dewey, "Existence, Value, and Criticism" from Experience and Nature

Much ink has been spilled lately on the role of religion in sports. The entire country, it seems, has been transfixed by Tim Tebow, as he marched onward in the NFL playoffs. Through his play, demeanor, and public pronouncements of faith, Mr. Tebow has asked us all to consider such strange questions as whether or not God takes sides in football games, whether religious faith can make you a better athlete, what role religion ought to play in public life, and exactly how much credit we should give (or take away) from Tebow for so boldly proclaiming his faith in our increasingly secular and pluralistic culture.

Before Tebow hit the NFL, we few followers of the sport of distance running already had our Tebow. Ryan Hall and Tim Tebow seem to carry themselves similarly. After he finished 2nd in Saturday's marathon trials, he talked about how God was with him for every step of the race. Hall left his coach, Terrence Mahon, and now talks about waking up in the middle of the night inspired by the insights that God has given him into his training.

It's important to remember that there have been a lot of great athletes who have reached the pinnacle of their sports without the same sort of evangelical zeal. History shows that this sort of open faith is unnecessary for athletic success. However, both Hall and Tebow are so convinced that their faith is the key to their performance that it is hard not to take their personal conviction seriously. The question they pose to us is simple, but stunning: "Would I be a better athlete--not to mention a better person--if I had the same sort of religious faith that Hall and Tebow did?" Both Hall and Tebow basically answer in all their words and actions, yes. They see their role as celebrities as a platform given to them by God in order to celebrate him and spread his messages.

Today we also celebrate a man who put his faith into action, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Reflecting a bit on his life, remembering the ends to which he put his religious belief, helps to put the question that Hall and Tebow pose to us in perspective. While both Tebow and Hall contribute to charity and practice good works, King took the lessons of Christianity to heart in a more profound way, focusing not on charity but on social justice. While Tebow and Hall speak eloquently of the power that God gives them in their personal lives and as they practice their professional sports, King preferred to emphasize the duties that God imposed upon him as a believer.

It seems to me that King's connection with God was much less personal and individual than the way Tebow or Hall characterize their connection. For King, God's greatest gift to humanity was the ability to dream of social justice, and to give ourselves in effort to actualize that dream. King was not content to proselytize through celebrity or games; these are essentially conservative social functions. He used his radical vision of religion to push an entire nation to change itself in fundamental ways.

When King was assassinated, he had moved through the issue of race to the issue of poverty, which he thought was a more fundamental concern. The day that he was shot, his approval rating stood at 30%. My grandmother, a Nashville native, spoke to me just last week of how much people hated Dr. King in her community--a fact that she herself had almost forgotten in the 44 years since his death.

When King was assassinated, he had moved through the issue of race to the issue of poverty, which he thought was a more fundamental concern. The day that he was shot, his approval rating stood at 30%. My grandmother, a Nashville native, spoke to me just last week of how much people hated Dr. King in her community--a fact that she herself had almost forgotten in the 44 years since his death.In the passage above, John Dewey draws our attention to two psychological extremes, both of which stem from the same weakness. The first extreme is overestimating our own power, believing that we are gods or that a god will bend the world to our own plans. The second extreme is disillusionment with the world: seeing the world as fundamentally broken and withdrawing from it to a dream world of idealism. I see both of these extremes in the internet discussions of the meaning of Tebow and Hall's successes. The "haters" impugn their idealism, calling them crazy. The "lovers" see in Tebow and Hall confirmation of their own personal vision of reality, evidence of the transformative power of Christianity.

Dewey was not a Christian, and neither am I. But he was a clear-eyed examiner of social life and the role of religious sentiment in it. I think he would have found both of these ways of seeing Tebow and Hall lacking.

The mature balance towards which Dewey pushes us, and which I would like to encourage as well, neither puts too much power in faith, nor too little. Athletes like Tebow and Hall can remind us of what Dewey calls "the juvenile assumption of power and achievement." Their naive belief in themselves and in their personal vision of the world is refreshing in a cynical age. But we should not forget that our cynicism and the tolerance that it can give us for other points of view and working through difficulties is also hard won--the product of ripened experience. This is why, for me, King provides a more complete vision of the role of faith in life. His faith focused not only on power and achievement, but turned him steadfastly towards the most difficult of problems: how to create lasting change for the better in this world.

King's democratic faith had an element of the blues in it. Cornel West called this element of faith a capacity for "tragicomic hope" -- the ability to dwell amid suffering, to confront the tragedies of the human condition, and to make a song out of it. Tebow and Hall are young, still. They are great representations of juvenile power, and they ought to inspire us with their power and performance. But King, to my mind, is the greater exemplar of a fully mature human faith. Like the man from whom his religion draws its power, his life is not a reminder of the power of the individual to forge its own destiny or do what he puts his mind to. The lesson is deeper. His life and faith is a reminder of the work that is left to be done on behalf of humanity: the duty of social justice.

King's life and faith preached "a dangerous unselfishness." He taught that the clear-eyed recognition of our duty to humanity is the mark of a belief that fully deserves to call itself religious.

One could argue that both Hall and Tebow put their faith into action, but you're right, not to at the level of MLK.

ReplyDeleteHey Dirk,

DeleteI think that's exactly the kind of argument I'm trying to make, but not quite sure. Thanks for the comment.

Jeff

Awesome, dude. But wait--I thought, as Chris Hitchens argued, religion is the cause of all problems in the world?

ReplyDeleteI appreciate Hitchens as a public intellectual, even though I think he's wrong about religion. He's a strong minded atheist, and the style of religion that he criticizes is bad--it's just not all of religion. Religion needs criticism from atheist quarters.

DeleteI guess what I like about both James and Dewey (and Cornel West and MLK) is that they show us common ground among religious folk and atheist folk. That's a pretty rare space.

here are some rather random thoughts. if they have taken root at all in me, it's a shallow root. they're just thoughts i had while reading this post so i wanted to share them. because i am generous like that. :)

ReplyDelete----------

you said -- The question they pose to us is simple, but stunning: "Would I be a better athlete--not to mention a better person--if I had the same sort of religious faith that Hall and Tebow did?"

i say -- the question they pose to me is: would tim or ryan be a lesser athlete, not to mention a lesser person, if not for his faith?

i mean, i wonder more what they'd be if they'd been raised differently, than i wonder what i would be had i been raised as they were.

-----------

can the difference in dr king's faith in duty as opposed to mr hall's and mr tebow's faith in power be attributed to the difference in how each was taught about their god? there is a difference in the southern black church of the 50s (40s?) where dr king was indoctrinated as a child, and the southern (?) white church of the 80s where the two young athletes were indoctrinated. i don't really know, see... what decade, what geographical location, what social location each of these men grew up in. but it's true that christianity is not uniformly taught, so i wonder how much of the difference between these men's beliefs and their actions can be attributed to their upbringings.

----------

dr king's depersonalization of his faith, the community-ization of it, allowed him to separate his personal actions from his religion. to put a fine point on it, dr king was not a faithful husband to his wife (or so i hear...). how could he reconcile his faith with this action? because to him, faith is something lived in community, impersonal, not in person.

----------

"The second extreme is disillusionment with the world: seeing the world as fundamentally broken and withdrawing from it to a dream world of idealism." this pretty much defines dr king's beliefs. doesn't it? "i have a dream"...? what am i missing here?

----------

and, last but not least... you have a typo here (should be "seem" not "seems"): Ryan Hall and Tim Tebow seems to carry themselves similarly.

Thanks for the plethora of unrooted thoughts. Those are my favorite kind--rhizomatic.

DeleteRhizome #1: I kinda think these guys have a huge religious bone in their bodies, and it was going to get expressed in some way, and they were lucky, probably to be born in a richly religious context so that they felt comfortable letting their freaky religious flag fly. Which makes them pretty centered people. Which probably helps make them successful.

Rhizome #2: YES! (There is too much to be said here, but absolutely in order to understand these differences we have to look at the community differences, their relation to class and race.

Rhizome #3: This is a good point.

Rhizome #4: Dewey was criticizing those who give up on the world to live in a dream world--either by postponing justice or happiness to the next life or by becoming self-righteous know it alls who can't relate to people, but who are fixated on ideals. King, to the contrary, encouraged us to connect the dreams with reality. That was his message: we can't be afraid to dream AND we can't be content to merely dream.

Rhizome #5: I am surprised I had only one typo. Gonna fix it now. Thanks.

I don't see depersonalization of faith as required or even beneficial to the "community-ization" of it. I'm getting in over my head here, but wouldn't Gandhi be an example of someone with a deeply personal, ever-growing faith that also pushed for fundamental change on a global scale.

ReplyDeleteI am also not sure that the contrast between Hall and Tebow "living out their faith" and MLK's experience results, at least not entirely, from a different view of the role of religion.

While Tebow and Hall both devote their lives to sport, they each clearly engage in a sport in which they excel.

Neither find themselves in the time and place that MLK did and neither possess the qualities that would equip them for such a task.

I don't expect we'll see Tebow in the front row at Boston with a "TIM" bib anytime soon.

The question all of these men raise for me is something along the lines of.."What time and place do I find myself in, and to what ends, relevant to that context, am I applying my capabilities? And to what extent is this based on my faith?"

awaldvogel -- thanks for the thoughtful reply, which complicates nicely the contrast I was trying to draw.

ReplyDeleteMaybe the distinction I was looking for was not personal/communal, but private/public. It seems to me that figures like King invite us into their vision and ask others to extend it. It's public in that sense. When Hall/Tebow talk, they talk as if God is their private companion, who is walking beside them, giving them power. But I feel a bit shut off from that power--this is the sense in which their version of faith seems to me to be intensely personal. I'm not convinced this is a proper response, but maybe it will do.

Your last way of phrasing the question is interesting. Maybe one difference between the "young" faith of Hall and Tebow and the "older/mature" faith of King is that Hall/Tebow's faith gives them power in a world that is set up to celebrate their strengths. They find themselves nicely adapted to their contexts. King, on the other hand, found himself out of place, segregated from the larger context of his life. His faith was a transformative faith--serving the purpose of the *transformation* of his context.

Great Post!...MLK RIP

ReplyDelete