What Does It Mean to Run Naturally?

Aristotle, in the Physics, opposes the natural to the artificial. He says that natural things have "their principle of motion or of standstill" in themselves, whereas the artificial is dependent on something else for its "principle." Understanding what he means takes a little unpacking, but I think doing so will shed light on some current movements that are motivated by the idea of running more naturally.

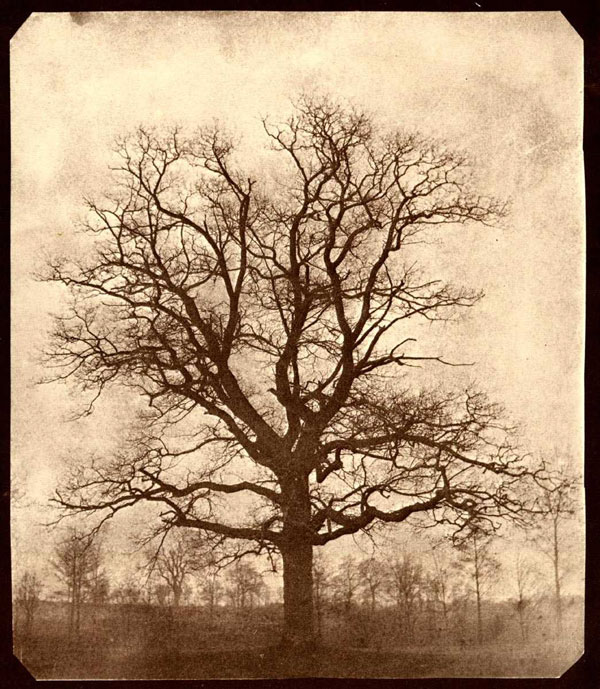

Aristotle describes the difference between the natural and the artificial using the example of a tree and a wooden bed frame. He notes that a tree's principle of growth is located within itself. It naturally follows the form of a tree, given the proper conditions, and it grows itself into a tree on its own. A wooden bedframe, notes Aristotle in one of the few moments of humor in his texts, will not grow into a bed when planted in the ground. In order that it take shape, the bed needs someone else to conceive of its idea. For this reason, we say that a bed is not natural, but artificial. It is a work of human art--it had to be conceived in the imagination and did not come into its own naturally but through the effort and mind of something outside of itself. The natural, therefore, is self-subsisting. The artificial is dependent in its very essence on something outside of itself.

Proponents of naturalism in running, then, see running as something we are born to do: read Born to Run, yet? On this view, we run as naturally as a tree develops branches and grows roots. Running is not a learned skill like medicine or architecture (do we naturally build skyscrapers or airplanes or MRI machines?), but something that is as native to the human condition as, say, having ears and toes. To rephrase Aristotle in terms of contemporary scientific discourse, you could say running is in our DNA.

As for me, I think running is a natural human activity, as far as this goes. We don't have to be taught how to run; running, like crawling and walking and speaking, emerges as a natural human capacity just like leaves grow on trees. But, in order to understand the implications of this for life today in 21st century America, we need to begin to look more carefully at the kind of running that we are talking about.

Running is a natural activity. Maybe even competitive distance running is natural. But the specific practice of racing 5ks and marathons that emerged in the 20th century seems to me to place the natural capacity of running in a set of very artificial circumstances. One characteristic of the natural is that it is seamlessly integrated with the rest of the world. A leaf grows out of a branch as part of a well-ordered organism. Competitive running and racing is not so integrated with the rest of life. It is something we do on the side, bearing only tangential relationships to the rest of our lives.

Few of us today in America use running as it emerged--as a means of locomotion, a way of getting from one place to another. We have other more advanced forms of travel now: automobiles, email, airplanes, trains, bicycles. So, running has this sort of strange position in contemporary life. It is a natural capacity of the human body, but our environment produces no demand to run. So, we have to artificially produce situations to run in our environment. We do this through racing and training. We would do the same thing tomorrow if, for example, the sun refused to shine. We would light the world with artificial bulbs because our eyes naturally want to see.

From an Aristotelian perspective, then, running more naturally is really an almost impossible task in the contemporary world. It is a natural need that will have to be satisfied artificially. But in order to construct better artificial running situations it is useful to remember the natural situation in which we run. This situation has less to do with the type of shoe that one wears, or whether one forsakes shoes at all, and much more to do with remembering that just as a tree sends its roots downward and its branches upward, the human body is constructed to be in a fairly constant state of locomotion. This is the natural situation. Getting back to nature, then, is less about footstrike and minimalism and more about finding ways to let the body move, constructing situations where we are forced to run in a variety of ways.

I think that this is what accounts for the current popularity of the marathon. Though the marathon is an artificial institution, it is a great way to reproduce a natural situation of a human body in constant motion. It compensates for the lack of natural stimulus to run in contemporary culture. It does so by producing a training situation, which is really just a plain old running situation. But the downside of a marathon is its status as a "bucket list" type of event. Insofar as the value of the marathon is conceived solely as an "accomplishment of willpower," its specific connection to the natural need for locomotion is erased. Under the sign of spiritual effort or willpower, the material needs of the body are lost as a primary justification for the event. The fact that completing a marathon is seen as an extraordinary thing is a sign of the way in which running is not naturally integrated into the rest of life.

This is the way culture seems to be trending in general. The demands of the mind--intellectual stimulation, bright flashing images, strange noises, the need to communicate--all of these needs are being met through the rise of virtual technologies. But the heady flights, the sense of being ungrounded, the dizziness and vertigo we feel after too much time spent in the virtual world are all effects of an overstimulated mind and an understimulated body. Why have certain aspects of human nature been stimulated to the point of grotesqueness while others have been understimulated? How have the institutions that we have built neglected certain aspects of our nature when they obviously care so much for other aspects (take, for example, the natural desire to hoard things)? Whose interests do these sorts of artificial institutions serve? And whose interests do they ignore?

These are the sorts of questions that come to my when I think about the desire to run naturally. The question is broad and complex, and we ought not reduce it to something that can be marketed as easily as a pair of Vibram Five-Fingers.

Aristotle describes the difference between the natural and the artificial using the example of a tree and a wooden bed frame. He notes that a tree's principle of growth is located within itself. It naturally follows the form of a tree, given the proper conditions, and it grows itself into a tree on its own. A wooden bedframe, notes Aristotle in one of the few moments of humor in his texts, will not grow into a bed when planted in the ground. In order that it take shape, the bed needs someone else to conceive of its idea. For this reason, we say that a bed is not natural, but artificial. It is a work of human art--it had to be conceived in the imagination and did not come into its own naturally but through the effort and mind of something outside of itself. The natural, therefore, is self-subsisting. The artificial is dependent in its very essence on something outside of itself.

The tree did this naturally, all by itself. The photograph, however, is a product of human artifice.

Proponents of naturalism in running, then, see running as something we are born to do: read Born to Run, yet? On this view, we run as naturally as a tree develops branches and grows roots. Running is not a learned skill like medicine or architecture (do we naturally build skyscrapers or airplanes or MRI machines?), but something that is as native to the human condition as, say, having ears and toes. To rephrase Aristotle in terms of contemporary scientific discourse, you could say running is in our DNA.

As for me, I think running is a natural human activity, as far as this goes. We don't have to be taught how to run; running, like crawling and walking and speaking, emerges as a natural human capacity just like leaves grow on trees. But, in order to understand the implications of this for life today in 21st century America, we need to begin to look more carefully at the kind of running that we are talking about.

Running is a natural activity. Maybe even competitive distance running is natural. But the specific practice of racing 5ks and marathons that emerged in the 20th century seems to me to place the natural capacity of running in a set of very artificial circumstances. One characteristic of the natural is that it is seamlessly integrated with the rest of the world. A leaf grows out of a branch as part of a well-ordered organism. Competitive running and racing is not so integrated with the rest of life. It is something we do on the side, bearing only tangential relationships to the rest of our lives.

Few of us today in America use running as it emerged--as a means of locomotion, a way of getting from one place to another. We have other more advanced forms of travel now: automobiles, email, airplanes, trains, bicycles. So, running has this sort of strange position in contemporary life. It is a natural capacity of the human body, but our environment produces no demand to run. So, we have to artificially produce situations to run in our environment. We do this through racing and training. We would do the same thing tomorrow if, for example, the sun refused to shine. We would light the world with artificial bulbs because our eyes naturally want to see.

We already have built environments when artificial light replaces natural light completely.

From an Aristotelian perspective, then, running more naturally is really an almost impossible task in the contemporary world. It is a natural need that will have to be satisfied artificially. But in order to construct better artificial running situations it is useful to remember the natural situation in which we run. This situation has less to do with the type of shoe that one wears, or whether one forsakes shoes at all, and much more to do with remembering that just as a tree sends its roots downward and its branches upward, the human body is constructed to be in a fairly constant state of locomotion. This is the natural situation. Getting back to nature, then, is less about footstrike and minimalism and more about finding ways to let the body move, constructing situations where we are forced to run in a variety of ways.

I think that this is what accounts for the current popularity of the marathon. Though the marathon is an artificial institution, it is a great way to reproduce a natural situation of a human body in constant motion. It compensates for the lack of natural stimulus to run in contemporary culture. It does so by producing a training situation, which is really just a plain old running situation. But the downside of a marathon is its status as a "bucket list" type of event. Insofar as the value of the marathon is conceived solely as an "accomplishment of willpower," its specific connection to the natural need for locomotion is erased. Under the sign of spiritual effort or willpower, the material needs of the body are lost as a primary justification for the event. The fact that completing a marathon is seen as an extraordinary thing is a sign of the way in which running is not naturally integrated into the rest of life.

Natural or unnatural?

This is the way culture seems to be trending in general. The demands of the mind--intellectual stimulation, bright flashing images, strange noises, the need to communicate--all of these needs are being met through the rise of virtual technologies. But the heady flights, the sense of being ungrounded, the dizziness and vertigo we feel after too much time spent in the virtual world are all effects of an overstimulated mind and an understimulated body. Why have certain aspects of human nature been stimulated to the point of grotesqueness while others have been understimulated? How have the institutions that we have built neglected certain aspects of our nature when they obviously care so much for other aspects (take, for example, the natural desire to hoard things)? Whose interests do these sorts of artificial institutions serve? And whose interests do they ignore?

These are the sorts of questions that come to my when I think about the desire to run naturally. The question is broad and complex, and we ought not reduce it to something that can be marketed as easily as a pair of Vibram Five-Fingers.

Excellent post.

ReplyDeleteRe:

"Getting back to nature, then, is less about footstrike and minimalism and more about finding ways to let the body move, constructing situations where we are forced to run in a variety of ways."

I almost entirely agree. The emphasis on foot strike comes from the observation that heel-striking is a very jarring way to run, and might be injurious. It's pretty much impossible to run on the heels when the feet are, shall we say, au natural.

Learning how to run fluidly and efficiently is important if you (general you, not you you) want to run and race happily for a long time. I would argue that running barefoot (for reals) is the easiest way to learn how, but don't think it's impossible to learn with pretty much any kind of shoe on.

Great stuff.

ReplyDeleteYou know, people used to walk to work (gasp!). I see the popularity of running as directly related to our dependency on automobiles.

Isn't that the story behind Kenyan running excellence--their kids don't take buses? We're so afraid of letting our kids be abducted that we drive them half a mile to school. Not a good way to let the body move naturally.

probably my favorite thing about running is the self-propulsion, the fact that i am moving myself by myself, and that's why it really doesn't bother me that i don't run fast or even that sometimes when i am "running" i am actually walking. i mean, i do like to run fast - it's a rush (rush... fast... haha!) but i don't feel compelled to "work on my speed". now that i am thinking about it, i think this is probably a part of why i hate treadmills so much - that whole going nowhere thing doesn't fulfill the need to self-propel, it doesn't have meaning, it's artificial. and, this is probably why i take the stairs. well, this, and the fact that elevators are not to be trusted. it's one of my favortive things about summer camp or about an solid urban area like NYC - you can get where you need to be on foot. there's a lot to think about here. maybe i should get a blog of my own. haha.

ReplyDeleteBarefootjosh, first off, thanks for commenting! I was hoping that a barefooter or two would comment. I agree that barefooting and minimalism can be a great way to learn to run. My off the cuff opinion is that the best reason why barefooting helps folks run better is because it increases proprioception, literally making the runner pay attention to his body. I just wanted to use Aristotle draw attention to the way in which running naturally is a broader issue than just footstrike or what sort of shoes than you wear. Sometimes I think there is a tendency to reduce the idea to this--maybe because it is a simple thing to do.

ReplyDeleteFinally, there's heel striking and heel striking. The folks at Science of Sport have done some really interesting stuff on footstrike. This piece (http://www.sportsscientists.com/2008/04/running-technique-footstrike.html) is a good place to start, but I encourage others to read all of their stuff on barefoot running and shoes--their views have grown more nuanced as the body of research has grown. Obviously good running form is about a variety of factors that include the whole body--just as there is a tendency sometimes to reduce "running naturally" to minimalism or barefooting, there is also a tendency to reduce form to footstrike. Both of these are important ways to analyze how to run better, but we should always be careful not to reduce complex issues to single issues just for the sake of having An Answer.

Thanks again for your comments; glad you are still reading!

Zach V,

ReplyDeleteThat's a great point. The automobile is a great thing, but it's had a lot of unintended consequences--from politics in the Middle East to health issues at home. I do think that a big reason why East Africans are strong distance runners is the lifestyle. I think we also have to recognize some sort of genetic component to their domination as well. I think that the field of epigenetics may help us analyze the issue even better. It could be that an active childhood or even adulthood "turns on" specific genes and may even determine which genes are then passed on, in an almost Lamarckian fashion.

Thanks for reading!

Hey ace,

ReplyDeleteI was thinking about this comment on my run today. There is something so satisfying about the immediacy of self-propulsion. I was also thinking about how running--when you get the right rhythm--requires no effort at all and is similar to a state of free-fall. Like a million little flights and landings. Since this is a post about Aristotle, it's worth saying that he liked to call humans "featherless bipeds." We have no feathers; we can't fly, but the closest approximation I've found is the bliss of an easy 10 miler.

Of course I'm reading - got to keep track of the competition (ha ha).

ReplyDeleteI understand the appeal of the "natural" argument - it's so tidy. And it's easier to say than "proprioception." Re heel striking, I think I can sum it up like this:

If you want to learn how to run barefoot, you can't land on your heel first without a lot of pain. If a shod runner runs in a way that wouldn't hurt if barefoot, overuse injuries are unlikely.

Other than that, the specifics of foot strikes don't really mean much to me. I try to let the foot land in a way that keeps me upright and moves me forward in the most comfortable way possible. Too many people (especially barefooters) look for "The Perfect Form" as if it were a static, rigid posture not to be deviated from. I think "Perfect Form" doesn't look like any one thing but rather is a constant flow of adjustments and deviations.

Which, I suppose, makes me a deviant.